Jews have lived in Poland since at least the Middle Ages. When Crusaders moved through Europe in the thirteenth century, Jewish refugees sought safety in Poland.Jews were treated well under the rule of Duke Boleslaw Pobozny (1221-1279) and King Kazimierz Wielki (1310-1370, aka King Casimir the Great ) because the now-decentralized nature of Polish polity saw the nobles forced to run their own areas and therefore the Jews, a group with commercial and administrative experience, were fought over to attract to the various townships.

Jews have lived in Poland since at least the Middle Ages. When Crusaders moved through Europe in the thirteenth century, Jewish refugees sought safety in Poland.Jews were treated well under the rule of Duke Boleslaw Pobozny (1221-1279) and King Kazimierz Wielki (1310-1370, aka King Casimir the Great ) because the now-decentralized nature of Polish polity saw the nobles forced to run their own areas and therefore the Jews, a group with commercial and administrative experience, were fought over to attract to the various townships.

In 1264, Duke Boleslaw issued the “Statute of Kalisz,” guaranteeing protection of the Jews and granting generous legal and professional rights, including the ability to become moneylenders and businessman. King Kasimierz ratified the charter and extended it to include specific points of protection from Christians, including guaranteed prosecution against those who “commit a depredation in a Jewish cemetery” and banning people from “accusing the Jews of drinking human blood.”

By the mid-1300’s, hatred of the Jews existed among the nobility. According to the Chronica Olivska, Jews throughout Poland were massacred because they were blamed for the Black Death. There were anti-Jewish riots in 1348-49 and again in 1407 and 1494 and Jews were expelled form the city of Cracow in 1495. However, by the mid-16th century, eighty percent of the world’s Jews lived in Poland. Jewish religious life thrived in the many Polish communities.

In 1648, a Ukrainian officer Bogdan Chmielnicki, with the support of the Tatar Khan of Crimea, roused the local peasants to fight with him and the Russian Orthodox Cossacks against the Jews. The first wave of violence in 1648 destroyed Jewish communities east of the Dnieper River. Following the violence, thousands of Jews fled west, across the river, to the major cities. The Cossacks and the peasants followed them; the first large-scale massacre took place at Nemirov (a small town, which is part of present-day Ukraine). It is estimated that 100,000-200,000 Jews died in the Chmielnicki revolt that lasted from 1648-1649. This wave of destruction is considered the first modern pogrom.

In 1648, a Ukrainian officer Bogdan Chmielnicki, with the support of the Tatar Khan of Crimea, roused the local peasants to fight with him and the Russian Orthodox Cossacks against the Jews. The first wave of violence in 1648 destroyed Jewish communities east of the Dnieper River. Following the violence, thousands of Jews fled west, across the river, to the major cities. The Cossacks and the peasants followed them; the first large-scale massacre took place at Nemirov (a small town, which is part of present-day Ukraine). It is estimated that 100,000-200,000 Jews died in the Chmielnicki revolt that lasted from 1648-1649. This wave of destruction is considered the first modern pogrom.

There were three partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and in 1795. Poland was divided among Russia, Prussia and Austria; Poland-Lithuania no longer existed. The majority of Poland’s one-million Jews became part of the Russian empire. Poland became a mere client state of the Russian empire. In 1772, Catherine II, empress of Russia; discriminated against the Jews by forcing them to stay in their shtetls and barring their return to the towns they occupied before the partition. This area was called the Pale of Settlement. By 1885, more than four million Jews lived in the Pale.

There were three partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and in 1795. Poland was divided among Russia, Prussia and Austria; Poland-Lithuania no longer existed. The majority of Poland’s one-million Jews became part of the Russian empire. Poland became a mere client state of the Russian empire. In 1772, Catherine II, empress of Russia; discriminated against the Jews by forcing them to stay in their shtetls and barring their return to the towns they occupied before the partition. This area was called the Pale of Settlement. By 1885, more than four million Jews lived in the Pale.

It is estimated that by 1772, before the frontiers of the Polish Republic began to recede, four-fifths of the world’s Jewish population were contained within them. This was hardly surprising, since they had been progressively expelled from every major state in Europe – from England in 1290, France in 1394, Spain in 1492, Portugal in 1497, Hungary in 1526 – while their nominal toleration in some of the German and Italian cities was belied by events. Poland alone never tried to expel them and encouraged their immigration. This was not so much the result of noble-mindedness as of a particular set of political and economic conditions. The expulsion of Jewish colonies from other countries had followed a strikingly similar pattern in which two motives were uppermost. The first was the eagerness of the native merchant class to eliminate the more efficient Jewish competitor. The second was supplied by the Church, sometimes in order to forestall a drift towards Judaism, more often as a means of showing its political power.

In the 1880s and 1890s, after the assassination of Russian Tsar Alexander II, Russian-Polish Jews were exposed to a series of organized massacres targeting Jewish communities called pogroms. In response, some two million Jews emigrated out of this region, with the vast majority going the United States. After World War I, Poland became a democratic independent state with significant minority populations, including Ukrainians, Jews, Belorussians, Lithuanians, and ethnic Germans. However, increasing Polish nationalism made Poland a hostile place for many Jews. A series of pogroms and discriminatory laws were signs of growing antisemitism, while fewer and fewer opportunities to emigrate were available.

In the 1880s and 1890s, after the assassination of Russian Tsar Alexander II, Russian-Polish Jews were exposed to a series of organized massacres targeting Jewish communities called pogroms. In response, some two million Jews emigrated out of this region, with the vast majority going the United States. After World War I, Poland became a democratic independent state with significant minority populations, including Ukrainians, Jews, Belorussians, Lithuanians, and ethnic Germans. However, increasing Polish nationalism made Poland a hostile place for many Jews. A series of pogroms and discriminatory laws were signs of growing antisemitism, while fewer and fewer opportunities to emigrate were available.

In 1918, Poland became a sovereign state. Following Poland’s rebirth, a reign of terror against the Jews began. Jews were massacred in pogroms by Poles who associated Trotsky and the Bolshevik revolution with Jewry (Trotsky was Jewish). Economic conditions declined for Polish Jews during the inter-war years. This economic downfall was accompanied by a rise of anti-Semitism. In the late 1930’s a new wave of pogroms befell the community and anti-Jewish boycotts were enacted.

In 1918, Poland became a sovereign state. Following Poland’s rebirth, a reign of terror against the Jews began. Jews were massacred in pogroms by Poles who associated Trotsky and the Bolshevik revolution with Jewry (Trotsky was Jewish). Economic conditions declined for Polish Jews during the inter-war years. This economic downfall was accompanied by a rise of anti-Semitism. In the late 1930’s a new wave of pogroms befell the community and anti-Jewish boycotts were enacted.

On September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, the Jewish population stood at 3.3 million. The German military killed about 20,000 Jews and bombed approximately 50,000 Jewish-owned factories, workshops and stores in more than 120 Jewish communities. Several hundred synagogues were destroyed in the first two months of occupation. Immediately, restrictions were placed on Polish Jews. One week before the invasion, Hitler signed a secret non-aggression pact (The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) with Soviet leader Josef Stalin. Russia subsequently invaded Poland on September 17, 1939. When the German-Russian War began, the areas previously controlled by Russia were incorporated into the Soviet Union. Of the 3.3 million Polish Jews at the outbreak of the war, about two million came under Nazi rule and the remainder were under Soviet occupation.

The first ghetto was started as early as October 1939 in Piorków Trybunalksi and was followed by the creation of ghettos in Lodz, Warsaw, Lublin, Radom and Lvov. By 1942, all Polish Jews were either confined to ghettos or hiding. That summer, the Nazis began liquidating the ghettos and within 18 months almost all of them had been emptied. In Warsaw, the largest ghetto was established on November 15, 1940. More than half a million Jews lived in the ghetto. About 300,000 Jews were deported to Treblinka on September 1, 1942. Jews received little food and the ghettos were overcrowded. Diseases such as typhus and tuberculosis were rife. Conditions worsened when Jews from small towns and other countries were squeezed in. It is estimated that 500,000 Jews died in the ghettos of disease and starvation. Many also perished in nearby slave labour camps, where conditions were even worse.

The first ghetto was started as early as October 1939 in Piorków Trybunalksi and was followed by the creation of ghettos in Lodz, Warsaw, Lublin, Radom and Lvov. By 1942, all Polish Jews were either confined to ghettos or hiding. That summer, the Nazis began liquidating the ghettos and within 18 months almost all of them had been emptied. In Warsaw, the largest ghetto was established on November 15, 1940. More than half a million Jews lived in the ghetto. About 300,000 Jews were deported to Treblinka on September 1, 1942. Jews received little food and the ghettos were overcrowded. Diseases such as typhus and tuberculosis were rife. Conditions worsened when Jews from small towns and other countries were squeezed in. It is estimated that 500,000 Jews died in the ghettos of disease and starvation. Many also perished in nearby slave labour camps, where conditions were even worse.

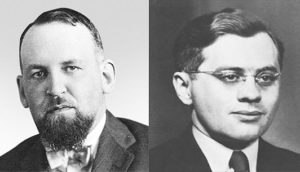

Dr. Eugeniusz Lazowski, a graduate of Warsaw University, is credited with saving approximately 8,000 Jews after putting his medical knowledge to use. Having injected the town’s Jews with a benign form of typhus he then informed the Nazis that an epidemic was at large. Terrified that it would spread, the Nazis quarantined the town and left it to its own devices. Known as ‘the Polish Schindler,’ Lazowski saved 12 ghetto communities in this crafty manner. In Kraków a gentile pharmacist named Tadeusz Pankiewicz was given special permission to remain in the ghetto and exploited this to lend aid to the Jews. Medicine and vaccines were distributed for free.

Dr. Eugeniusz Lazowski, a graduate of Warsaw University, is credited with saving approximately 8,000 Jews after putting his medical knowledge to use. Having injected the town’s Jews with a benign form of typhus he then informed the Nazis that an epidemic was at large. Terrified that it would spread, the Nazis quarantined the town and left it to its own devices. Known as ‘the Polish Schindler,’ Lazowski saved 12 ghetto communities in this crafty manner. In Kraków a gentile pharmacist named Tadeusz Pankiewicz was given special permission to remain in the ghetto and exploited this to lend aid to the Jews. Medicine and vaccines were distributed for free.

In 1940, a year before the Nazis started deporting Jews to death camps, Joseph Stalin ordered the deportation of approximately 200,000 Polish Jews from Russian-occupied Eastern Poland to forced labor settlements in the Soviet interior. As cruel as Stalin’s deportations were, in the end they largely saved Polish Jewish lives, for the deportees constituted the overwhelming majority of Polish Jews who escaped the Nazi Holocaust. Of the survivors, approximately 80% escaped the Holocaust as a result of Stalin’s deportation deep into the Soviet Union.

The Soviet-occupied zone of Poland fell into German hands following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Killing squads called Einsatzgruppen rounded up and shot Jewish men, women and children, as well as communist officials and others considered racially or ideologically dangerous. Surviving Jews were forced into ghettos. On 21 July 1942 the Nazis began the ‘Gross-Aktion Warsaw’, the operation of mass-deportation of Jews in the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka death camp, 80 km north-east.

The Soviet-occupied zone of Poland fell into German hands following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Killing squads called Einsatzgruppen rounded up and shot Jewish men, women and children, as well as communist officials and others considered racially or ideologically dangerous. Surviving Jews were forced into ghettos. On 21 July 1942 the Nazis began the ‘Gross-Aktion Warsaw’, the operation of mass-deportation of Jews in the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka death camp, 80 km north-east.

German Nazis established six extermination camps throughout occupied Poland by 1942. All of these – at Chełmno (Kulmhof), Bełżec, Sobibór, Treblinka, Majdanek and Auschwitz (Oświęcim) – were located near the rail network so that the victims could be easily transported. The system of the camps was expanded over the course of the German occupation of Poland and their purposes were diversified; some served as transit camps, some as forced labor camps and the majority as death camps. While in the death camps, the victims were usually killed shortly after arrival, in the other camps able-bodied Jews were worked and beaten to death.

In January 1943, the Nazis tried to start another round of deportations, however, they were stopped after four days due to Jewish resistance. On April 19, 1943, the German army entered the ghetto and was met again by fierce opposition. It took several months, until June 1943, before the ghetto was liquidated. The Warsaw ghetto uprising reverberated throughout Poland and the rest of the world as an example of courage and defiance.

Simcha Rotem, nicknamed ‘Kazik,’ was one of Jewish fighters from the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising against the Nazis. The Jewish fighters battled for nearly a month, fortifying themselves in bunkers and managing to kill 16 Nazis and wound nearly 100. Though guaranteed to fail, the Warsaw ghetto uprising symbolised a refusal to succumb to Nazi atrocities and inspired other resistance campaigns by Jews and non-Jews alike. Others who helped the Jews in the ghetto include: Irena Sandler, a Polish nurse, was one of the brave Poles who saved at least 2,500 children from the Warsaw Ghetto. Toolboxes, potato sacks, coffins; these were some of the methods used by the group to smuggle the children out. A Catholic church on the border also provided a rare escape route, alongside numerous underground tunnels.

Simcha Rotem, nicknamed ‘Kazik,’ was one of Jewish fighters from the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising against the Nazis. The Jewish fighters battled for nearly a month, fortifying themselves in bunkers and managing to kill 16 Nazis and wound nearly 100. Though guaranteed to fail, the Warsaw ghetto uprising symbolised a refusal to succumb to Nazi atrocities and inspired other resistance campaigns by Jews and non-Jews alike. Others who helped the Jews in the ghetto include: Irena Sandler, a Polish nurse, was one of the brave Poles who saved at least 2,500 children from the Warsaw Ghetto. Toolboxes, potato sacks, coffins; these were some of the methods used by the group to smuggle the children out. A Catholic church on the border also provided a rare escape route, alongside numerous underground tunnels.

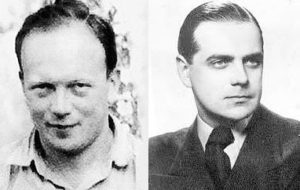

Aleksander Ładoś, a Polish envoy to Bern during the Second World War and Juliusz Kühl, a Polish-born Swiss citizen attempted to save thousands, of lives by purchasing a blank South American passports. Jews holding passports from neutral countries were considered exempt from Nazi laws that confined Jews to ghettos and mandated that they identify themselves by wearing yellow stars on their clothing. Those third-country passports allowed many Jews to flee ahead of the mass exterminations that followed. Germans left them alone because they could prove useful to trade for German citizens held captive abroad. However, Germany, noticed the large amount of South American passport holders, and found these were fake, and the holders were deported.

Aleksander Ładoś, a Polish envoy to Bern during the Second World War and Juliusz Kühl, a Polish-born Swiss citizen attempted to save thousands, of lives by purchasing a blank South American passports. Jews holding passports from neutral countries were considered exempt from Nazi laws that confined Jews to ghettos and mandated that they identify themselves by wearing yellow stars on their clothing. Those third-country passports allowed many Jews to flee ahead of the mass exterminations that followed. Germans left them alone because they could prove useful to trade for German citizens held captive abroad. However, Germany, noticed the large amount of South American passport holders, and found these were fake, and the holders were deported.

The Hungarian government tolerated the entry of Jewish refugees from neighboring Poland and Slovakia and generally did not deport Hungarian Jews to German-occupied territory. After the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944, however, Hungarian authorities deported both Hungarian Jews and Polish Jewish refugees alike. The Germans murdered the majority in Auschwitz-Birkenau in the spring and summer of 1944.

Eighty-five percent of Polish Jewry perished in the Holocaust. Following the Holocaust when Jewish individuals who fled from Poland attempted to return to their homes and villages they faced a new wave of anti-Semitism and skepticism. Many survivors fled to Romania and Germany in hope of reaching Palestine. Those who remained attempted to rebuild Jewish life in the 200 local communities. Jews were still subject to anti-Semitism and pogroms. The Kielce Pogrom in July 1946, in which 40 Jews were killed, was the impetus for another mass emigration. At the end of 1947, only 100,000 Jews remained in Poland.

Eighty-five percent of Polish Jewry perished in the Holocaust. Following the Holocaust when Jewish individuals who fled from Poland attempted to return to their homes and villages they faced a new wave of anti-Semitism and skepticism. Many survivors fled to Romania and Germany in hope of reaching Palestine. Those who remained attempted to rebuild Jewish life in the 200 local communities. Jews were still subject to anti-Semitism and pogroms. The Kielce Pogrom in July 1946, in which 40 Jews were killed, was the impetus for another mass emigration. At the end of 1947, only 100,000 Jews remained in Poland.

The Soviet Union’s secret police essentially governed the country and Stalin’s anti-Semitic regime stifled Jewish cultural and religious activities. Jewish schools were nationalized in 1948-49 and Yiddish was no longer used as the language of instruction. Stalin’s death in 1953 eased the situation for the Jews and in the 1958-59 period, 50,000 Jews emigrated to Israel, which was the only country Jews were able to immigrate to under Polish law.

Most of the remaining Jews left Poland in late 1968 as the result of the “anti-Zionist” purge, when more than 15,000 Jews were stripped of citizenship and forced to leave. As a result, less than a tenth of the 10% of Polish Jews who managed to survive the Holocaust remained. After the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, the situation of Polish Jews became normalized and those who were Polish citizens before World War II were allowed to renew Polish citizenship.

Most of the remaining Jews left Poland in late 1968 as the result of the “anti-Zionist” purge, when more than 15,000 Jews were stripped of citizenship and forced to leave. As a result, less than a tenth of the 10% of Polish Jews who managed to survive the Holocaust remained. After the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, the situation of Polish Jews became normalized and those who were Polish citizens before World War II were allowed to renew Polish citizenship.

Until the 1990s, many Polish Jews didn’t even know they were Jewish. Most who survived the Holocaust left the country in subsequent decades, while those who stayed hid their identity for the remaining decades of communism. Only after the fall in 1989, their children and grandchildren began to discover their true roots and confront their new identities. The Union of Jewish Religious Communities in Poland was founded in 1993. Its purpose is the promotion and organization of Jewish religious and cultural activities in Polish communities.

On July 4, 2006, a memorial to Holocaust survivors killed and wounded in Kielce, Poland after World War II will was unveiled. The Jewish Community Centre of Krakow (JCC) which officially opened in April 2008 in a purpose-built, new building on Miodowa Street nearby the historic reformed Tempel synagogue, seems to have become the most important new institution providing social, educational and community-oriented services to the Jewish community of Krakow.

On July 4, 2006, a memorial to Holocaust survivors killed and wounded in Kielce, Poland after World War II will was unveiled. The Jewish Community Centre of Krakow (JCC) which officially opened in April 2008 in a purpose-built, new building on Miodowa Street nearby the historic reformed Tempel synagogue, seems to have become the most important new institution providing social, educational and community-oriented services to the Jewish community of Krakow.

The POLIN is the museum of the History of Polish Jews opened in 2014. Over $300 million was spent from various sources building a museum that tells the story of 800 years of Jewish life in Poland. This was the largest sum of money ever spent on any cultural institution in Polish history.

Polish Jewish is estimated at between 10,000 and 20,000 members. There are two rabbis serving the Polish Jewish community and several Jewish schools. A large number of cities with synagogues include Warsaw, Kraków, Zamość, Tykocin, Rzeszów, Kielce, or Góra Kalwaria, although not many of them are still active in their original religious role. Stara Synagoga (“Old Synagogue”) in Kraków, which hosts a Jewish museum, was built in the early 15th century and is the oldest synagogue in Poland. Warsaw has an active synagogue, Beit Warszawa, affiliated with the Liberal-Progressive stream of Judaism. The Noyzk Synagogue is the only shul in Warsaw out of 400 to have survived the war.

Polish Jewish is estimated at between 10,000 and 20,000 members. There are two rabbis serving the Polish Jewish community and several Jewish schools. A large number of cities with synagogues include Warsaw, Kraków, Zamość, Tykocin, Rzeszów, Kielce, or Góra Kalwaria, although not many of them are still active in their original religious role. Stara Synagoga (“Old Synagogue”) in Kraków, which hosts a Jewish museum, was built in the early 15th century and is the oldest synagogue in Poland. Warsaw has an active synagogue, Beit Warszawa, affiliated with the Liberal-Progressive stream of Judaism. The Noyzk Synagogue is the only shul in Warsaw out of 400 to have survived the war.