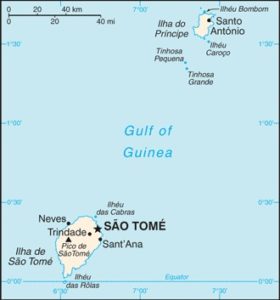

King Manuel I of Portugal exiled about 2,000 Jewish children under the age of ten, whose parents were unable to pay a head tax to São Tomé and Príncipe around 1500. When the parents of the children saw that the deportation was inevitable, they impressed on the children the importance of keeping the Laws of Moses; and some even married the children off to each other.

King Manuel I of Portugal exiled about 2,000 Jewish children under the age of ten, whose parents were unable to pay a head tax to São Tomé and Príncipe around 1500. When the parents of the children saw that the deportation was inevitable, they impressed on the children the importance of keeping the Laws of Moses; and some even married the children off to each other.

The entreaties of the parents apparently did not go in vain; for reports reached the Office of The Inquisition in Lisbon that in Sao Thome e Principe there were incidents of obvious Jewish observance. The Roman Catholic Church was greatly incensed. The Roman Catholic bishop appointed to San Thome e Principe in 1616, Pedro da Cunha Lobo, became obsessed with the problem.

According to an historical source, on Simhath Torah 1621, he was awakened by a procession, rushed out to confront them, and was so heartily abused by the demonstrators that in disgust he gave up and took the next ship back to Portugal.

Similarly, a number of Portuguese ethnic Jews were exiled to São Tomé after forced conversions to Catholicism.

There was a small influx of Jewish cocoa and sugar traders to the islands in the 19th and 20th centuries, two of whom are buried in the Sao Thome e Principe cemetery.

There was a small influx of Jewish cocoa and sugar traders to the islands in the 19th and 20th centuries, two of whom are buried in the Sao Thome e Principe cemetery.

Although Jewish practices faded over subsequent centuries, there are people in São Tomé and Príncipe who are aware of partial descent from this population.

The descendants of the child slaves are still a very distinctive section of the population, distinguished by their by their whiter skins, proud of their historic past and desirous of contact with Jews outside. Some Jewish customs seem to have continued, although by now mixed with heavy Creole society values and culture.

Today there are no known “practicing” Jews on the islands, but the descendants of these exiled children have expressed interest in learning more about the customs of their ancestors.