Venta Prieta, founded in the 1850s, was a small Mexican community which carefully guarded its Jewish identity. Its founders and most of its inhabitants were descendants of families who had spent 300 years hiding in Mexico’s mountains after escaping the Spanish Inquisition. The community’s founders, a couple named Tellez, who settled in Venta Prieta when it was just an outpost.

Venta Prieta, founded in the 1850s, was a small Mexican community which carefully guarded its Jewish identity. Its founders and most of its inhabitants were descendants of families who had spent 300 years hiding in Mexico’s mountains after escaping the Spanish Inquisition. The community’s founders, a couple named Tellez, who settled in Venta Prieta when it was just an outpost.

The Jews of Venta Prieta say their ancestors remained Jews throughout the Inquisition, even though they had no synagogue and no rabbi to instruct them during the centuries of hiding. They did not eat pork or mix milk and meat, and virtually all the men were circumcised. They observed of the Shabbat, and had public prayers in the local synagogue during Friday evenings and Saturday mornings. The prayers were mostly in Spanish and sometimes in Hebrew. The community could trace its lineage back to the early nineteenth century. In the last 50 years, they built their own temple, bought their own Torah, and, in keeping with biblical tradition, have had an eternal flame of olive oil-which requires constant attention burning inside the temple.

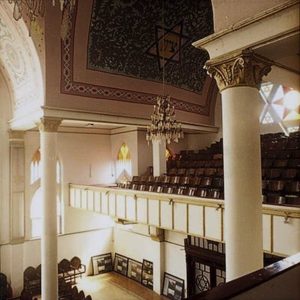

Venta Prieta’s synagogue stands behind a forbidding white wall, but a secret little door opens onto a courtyard filled with bouncing children, whose faces represent a cross pollination of continents: Europe, North Africa, Indo-America. Rough blue and yellow stained glass windows with elongated Stars of David ring the small temple. Inside, rows of old wooden pews with separate chair backs and armrests seat about 100 people. The Sacred Ark, which houses the Torah, is made of marble and onyx. A white polyester curtain with two fierce lions of Judah sewn in sequins covers the Sacred Ark. Next to it, a flame flickers in a silver bowl filled with olive oil.

At the front of the synagogue is a marble-lined ark; the rest of the room is taken up by rows of high-backed wooden chairs, divided in the middle by a mehitzah to separate the men and women during prayer. Replicas of Chagall’s Twelve Tribes of Israel hang around the wall. The community built a new temple after the war, and a bigger one in 1967. In the 1960s, they openly identified themselves as Jewish for the first time. The new generation felt more secure and began seeking Hebrew books and schooling. The only Hebrew the elders could read was the Hebrew of the prayers, and they wanted to know more.

The community learned to speak Hebrew, and young people began taking trips to Israel through international Jewish organizations. Returning with language and knowledge, the young instruct the old in ancient tradition. Its Jewish community now numbers about 200. And a few months ago, it received its first full-time rabbi, an Orthodox Argentinian. Plans were issued for the building of a new mikveh due to replace the old structure dating from 1972 and located inside the synagogue. In addition there are a community centre and a cemetery. However, the main Jewish organizations do not recognize them as Jews.