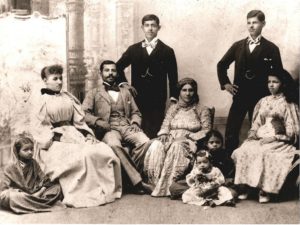

The first wave of Jewish immigration arrived in China as a result of the Opium War and the subsequent upsurge of trade with Britain. Coming to China from British-controlled places such as Baghdad, Bombay, and Singapore, most of these were merchants and businessmen with British citizenship. Originally from Baghdad, the Sassoon family first shifted their operations eastward to India and then went on to become the first Jews to establish firms and engage in business in Hong Kong (1841) and Shanghai (1845). Other Sephardi such as the Hardoons and Kadoories also came to China to seek their fortunes.

The first wave of Jewish immigration arrived in China as a result of the Opium War and the subsequent upsurge of trade with Britain. Coming to China from British-controlled places such as Baghdad, Bombay, and Singapore, most of these were merchants and businessmen with British citizenship. Originally from Baghdad, the Sassoon family first shifted their operations eastward to India and then went on to become the first Jews to establish firms and engage in business in Hong Kong (1841) and Shanghai (1845). Other Sephardi such as the Hardoons and Kadoories also came to China to seek their fortunes.

Hong Kong and Shanghai became their leading bases for business. They soon revealed their commercial talents, taking advantage of their traditional contacts with various British dependencies as well as the favorable geographic location of Shanghai and Hong Kong to develop a thriving import-export trade from which they quickly became wealthy.

They invested this wealth in real estate, finance, public works and manufacturing, becoming the most active foreign consortium in Shanghai and Hong Kong. They were also built synagogues, established schools, and provided aid to Russian Jewish immigrants and European Jewish refugees. They supported the Zionist movement and maintained cordial relations with the social and political groups in China. The community had its own synagogues, schools, hospitals, clubs, cemeteries, chamber of commerce, more than 50 publications, active political groups and a small fighting unit – Jewish Company of Shanghai Volunteer Corps, which was at the time the world’s sole legal Jewish regular army.

There was a second wave of Jews from Russian fleeing pogroms and revolution. Facing anti-Semitic persecution in Russia, many Jews took up the Czarist Government’s invitation to move east across Siberia to Manchuria, where the East China Railway was being built to Vladivostok under a concession forced from China’s Qing Dynasty. The Jewish migration gained momentum after the 1905 Russian-Japanese War, and further increased after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

The third wave of immigration corresponded to refugees fleeing Europe to escape the Nazi regime. After 1938, almost all countries closed their doors to Jews trying to escape. The Chinese city of Shanghai was a free port and did not require visas. Thus, from 1933 to 1941, Shanghai accepted over 30,000 European Jewish refugees. By the time of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour, in December 1941, the city was sheltering 20,000-25,000 Jewish refugees.

Japan occupied Shanghai in World War II but refused Nazi orders to deport or murder the city’s Jews. The 20,000 stateless Jewish refugees still in the city were confined in what became known as the Hongkew ghetto, but those with jobs outside were permitted to continue working. The Iraqi and Russian Jewish communities, along with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, sent in frequent aid. Disease and poverty were rampant, but the Jews of Shanghai were spared the horrors of the Holocaust.

Today, the Jewish communities of China consist primarily of those in Hong Kong, with about 3500; Shanghai, with about 1000; and Beijing, with at least 200. Hong Kong has a longstanding, permanent Jewish community as well as a transitory business one; the Shanghai and Beijing Jewish communities are mostly

transitory business or government related people.

As of 2010, it is estimated that 2,000 to 3,000 Jews lived in Shanghai. In May 2010, the Ohel Rachel Synagogue in Shanghai was temporarily reopened to the local

Jewish community for weekend services.