Jewish occupation in Guernsey dates back to well before the events of 1940-5. A London Jew named Abraham was described in 1277 as being from “La Gelnseye” (Guernsey). A converted Portuguese Jew, Edward Brampton, was appointed Governor of Guernsey in 1482.

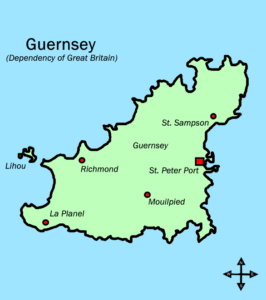

Guernsey’s Jewish population has historically been much smaller than that of neighboring Jersey, and there has never been a synagogue on the island. Enemy aliens, people born in a country with which Britain was at war, were restricted from entering Britain without a permit. Accordingly, a few Jews became trapped in Guernsey when the islands were occupied. In addition, a few locals decided to remain in Guernsey rather than evacuate in June 1940.

The deportation of the Jews from the Channel Islands was with the full connivance of the bailiffs and the government authorities. The history of Guernsey’s delivery of the Jews to the Nazis was concealed for decades.

A plaque commemorating three Jewish victims of the Holocaust in Guernsey was created to commemorate the three women deported from the Channel Island to the coast of France in 1942 and eventually gassed in Auschwitz. The plaque reads: To the memory of Marianne Grunfeld, Auguste Spitz, Therese Steiner, Jewish residents of Guernsey deported to France by the German occupying forces on 21 April 1942.

One Jewish woman hid in plain sight from the Nazis in Guernsey. It seems likely she was protected by a senior member of the island’s government who was possibly her lover. Ms Jay had been born in London and grew up in a Jewish family. She moved to Guernsey in 1932 and changed her surname from the Jewish-sounding Jacobs in 1937 – at a time when anti-Semitism was on the rise. After her wartime experience, she returned in the 1960s to Essex where she spent the remainder of her life.

Alderney, is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands and part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey. In June 1940, the entire population of Alderney, about 1,500 residents, were evacuated. Most went on the official evacuation boats sent from mainland Britain. The Germans fortified Alderney as part of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall. In January 1942 they built four camps in Alderney: two work camps, Lager Helgoland and Lager Borkum, and two concentration camps, Lager Sylt and Lager Norderney. The jail behind the main police station was used by the Nazis as a prison. The island’s prisoners were mostly from Ukraine, Poland, Russia and other Soviet territories, but there were also a significant number of French Jews. In March 1943, Sylt, already known to be the harshest labor camp on Alderney, became a concentration camp run by Adolf Hitler’s SS paramilitary.

This grim transformation into a concentration camp used to hold political prisoners and other perceived enemies of the state saw Sylt expand from housing just a few hundred prisoners to more than 1,000 detainees. The death toll for all of the camps on Alderney was at least 700. Prisoners were subject to substandard living conditions, exposure, malnutrition, beatings, and even summary executions. The prisoners performed forced labour for up to 16 hours per day, 7 days a week, with occasional 24-hour work periods interrupted only by half a day’s rest.

Breakfasts consisted of a cup of herbal tea that ‘tasted like copper’. Lunch was a thin cabbage soup, and dinner more cabbage soup with bread and occasionally 10-15 grams of margarine.

Breakfasts consisted of a cup of herbal tea that ‘tasted like copper’. Lunch was a thin cabbage soup, and dinner more cabbage soup with bread and occasionally 10-15 grams of margarine.

Prisoners slept in lice-ridden barracks on pallets using straw for warmth, as there were no blankets. No drinking water was available in the camp. Jews were forced to work for 60-hour stretches with 12-hour rest periods. Many of the Jews who survived Norderney were later deported from France to concentration camps in Germany and extermination camps in Eastern Europe.

When the Germans retreated from Alderney in 1944, they took pains to cover their tracks, however archaeologists have combined existing historical knowledge, including testimonials from former prisoners, with modern methods such as aerial surveys, ground-penetrating radar and laser mapping to unearth Sylt’s story.