The first real major wave of Jewish immigrants spread through Walachia (a Romanian principality founded around 1290) after they had been expelled from Hungary in 1367. In the 16th century some refugees from the Spanish expulsion came to Walachia from the Balkan Peninsula. At the beginning of the 16th century there were Jewish communities in several Moldavian towns, such as Jassy (Iasi), Botosani, Suceava, and Siret. More intensive waves of Jewish immigration resulted from the Chmielnicki massacres (1648–49). From the beginning of the 18th century, the Moldavian rulers granted special charters to attract Jews (exemption from taxes, ground for prayer houses, ritual baths, and cemeteries). Spanish Jews’ settlement in Romania can be divided into two distinct periods. In the first period, from 1496–1730, the Sephardic community flowed from Nikopol, Thessaloniki, Sarajevo, Istanbul, and Izmir, and gradually established a settlement with Sephardic traditions in Romania. In the second period, starting in 1730, the Spanish Jewish community received official recognition.

The first real major wave of Jewish immigrants spread through Walachia (a Romanian principality founded around 1290) after they had been expelled from Hungary in 1367. In the 16th century some refugees from the Spanish expulsion came to Walachia from the Balkan Peninsula. At the beginning of the 16th century there were Jewish communities in several Moldavian towns, such as Jassy (Iasi), Botosani, Suceava, and Siret. More intensive waves of Jewish immigration resulted from the Chmielnicki massacres (1648–49). From the beginning of the 18th century, the Moldavian rulers granted special charters to attract Jews (exemption from taxes, ground for prayer houses, ritual baths, and cemeteries). Spanish Jews’ settlement in Romania can be divided into two distinct periods. In the first period, from 1496–1730, the Sephardic community flowed from Nikopol, Thessaloniki, Sarajevo, Istanbul, and Izmir, and gradually established a settlement with Sephardic traditions in Romania. In the second period, starting in 1730, the Spanish Jewish community received official recognition.

Trouble for the Jews began in 1821, with the first stirrings of Romanian independence and unity. In the course of the rebellion against the Turks, Greek volunteers crossed Moldavia on their way to the Danube, plundering and slaying Jews as they went. Moldavia and Walachia were occupied by Russia, under whose influence anti-Semitism increased. Jews were forbidden to settle in villages, to lease lands, and to establish factories in towns. Citizenship was denied to Jews. In 1859; Alexandru Ioan Cuza became the sovereign. The number of Jews was then 130,000. In 1864, native Jews were granted suffrage in the local councils, but not

foreign subjects. In 1866, he was ousted by anti-liberal forces. A new sovereign, Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, was elected and during this time the Choir Temple in Bucharest was demolished and the Jewish quarter plundered. Citizenship was restricted to the Christian population. The following year Jews began to be discriminated against and expelled.

The situation of the Jews continued to grow worse. Jews had been considered Romanian subjects, but now they were declared to be foreigners. The Romanian government persuaded Austria and Germany to withdraw their citizenship from Jews living in Romania. The Jews were forbidden to be lawyers, teachers, chemists, stockbrokers, or to sell commodities that were a government monopoly (tobacco, salt, alcohol). They were not accepted as railway officials, in state hospitals, or as officers. Jewish pupils were later expelled from the public schools (1893). Meanwhile political intimidation continued. In 1885, some of the Jewish leaders and journalists who had participated in the struggle for emancipation.

The situation of the Jews continued to grow worse. Jews had been considered Romanian subjects, but now they were declared to be foreigners. The Romanian government persuaded Austria and Germany to withdraw their citizenship from Jews living in Romania. The Jews were forbidden to be lawyers, teachers, chemists, stockbrokers, or to sell commodities that were a government monopoly (tobacco, salt, alcohol). They were not accepted as railway officials, in state hospitals, or as officers. Jewish pupils were later expelled from the public schools (1893). Meanwhile political intimidation continued. In 1885, some of the Jewish leaders and journalists who had participated in the struggle for emancipation.

Up to World War I, about 70,000 Jews left Romania. From 266,652 in 1899, the Jewish population declined to 239,967 in 1912. The 1907 revolt of the peasants, who at first vented their wrath on the Jews, also contributed to this tendency to emigrate. Meanwhile, the persecution of the Jews increased. Their expulsion from the villages assumed such proportions that in some counties of Moldavia (Dorohoi, Jassy, Bacau), none remained except veterans of the 1877 war. Following World War I, Romania enlarged her territory with the provinces of Bukovina, Bessarabia, and Transylvania. In each of these the Jews were already citizens, either of long standing like those who had lived in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, or more recent such as those from Bessarabia who achieved equality only in 1917. Indeed, the naturalization of the Jews of Romania was under way in accordance with the separate peace treaty concluded with Germany in the spring of 1918. Growing social and political tensions in Romania in the 1920s and ’30s led to a constant increase in anti-Semitism and in the violence that accompanied it. Anti-Semitic excesses and demonstrations expressed both popular and student anti-Semitism and cruelty.

Up to World War I, about 70,000 Jews left Romania. From 266,652 in 1899, the Jewish population declined to 239,967 in 1912. The 1907 revolt of the peasants, who at first vented their wrath on the Jews, also contributed to this tendency to emigrate. Meanwhile, the persecution of the Jews increased. Their expulsion from the villages assumed such proportions that in some counties of Moldavia (Dorohoi, Jassy, Bacau), none remained except veterans of the 1877 war. Following World War I, Romania enlarged her territory with the provinces of Bukovina, Bessarabia, and Transylvania. In each of these the Jews were already citizens, either of long standing like those who had lived in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, or more recent such as those from Bessarabia who achieved equality only in 1917. Indeed, the naturalization of the Jews of Romania was under way in accordance with the separate peace treaty concluded with Germany in the spring of 1918. Growing social and political tensions in Romania in the 1920s and ’30s led to a constant increase in anti-Semitism and in the violence that accompanied it. Anti-Semitic excesses and demonstrations expressed both popular and student anti-Semitism and cruelty.

Marshal Ion Antonescu, the military dictator of Romania from 1940-1944, advocated a policy of ethnic cleansing to purify the Romanian nation no less radical than Hitler’s own racial ideology. Yet, these atrocities were largely confined to the areas of present day South-West Ukraine, namely Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and Transnistria, which Romania conquered from the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. The cleansing of these provinces took two forms; mass shootings and deportation to ghettos and concentration camps, where the survivors were to be starved to death. In the first wave of the extermination campaign in the summer of 1941, the Romanian Army, aided by local officials and Ukrainians, carried out a wave of massacres and pogroms throughout Southwest Ukraine. Iasi, was the first of these massacres; other notable instances of mass shootings occurred in Odessa and Kishniviv. In each case thousands of Jews were rounded by the Romanian Army and local police forces and shot en masse. Transnistria was the centre of Antonescu’s extermination campaign; roughly 150,000 of the surviving Ukrainian and Romanian Jews from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina were deported to this territory between the Bug and Dniester rivers. Almost all of them perished, giving Transnistria the sinister nickname as the Romanian Auschwitz. Deportation itself was also a death sentence, with thousands of Jews dying en route to Transnistria in overcrowded railway cars.

Marshal Ion Antonescu, the military dictator of Romania from 1940-1944, advocated a policy of ethnic cleansing to purify the Romanian nation no less radical than Hitler’s own racial ideology. Yet, these atrocities were largely confined to the areas of present day South-West Ukraine, namely Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and Transnistria, which Romania conquered from the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941. The cleansing of these provinces took two forms; mass shootings and deportation to ghettos and concentration camps, where the survivors were to be starved to death. In the first wave of the extermination campaign in the summer of 1941, the Romanian Army, aided by local officials and Ukrainians, carried out a wave of massacres and pogroms throughout Southwest Ukraine. Iasi, was the first of these massacres; other notable instances of mass shootings occurred in Odessa and Kishniviv. In each case thousands of Jews were rounded by the Romanian Army and local police forces and shot en masse. Transnistria was the centre of Antonescu’s extermination campaign; roughly 150,000 of the surviving Ukrainian and Romanian Jews from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina were deported to this territory between the Bug and Dniester rivers. Almost all of them perished, giving Transnistria the sinister nickname as the Romanian Auschwitz. Deportation itself was also a death sentence, with thousands of Jews dying en route to Transnistria in overcrowded railway cars.

There were a number of people who helped the Jews in Romania.These included: Dr. Traian Popvici, Prince Constantin Karadja, Elena, the Queen Mother of Romania, Rozalia Antal, Anghel Anuţoiu, and Dumitru Beceanu.

Though Antonescu’s regime actively persecuted the native Jewish population in “Old” Romania, they were not massacred or deported as in South-West Ukraine. Dr. Traian Popvici protested to the governor and to Antonescu, arguing that the Jews were vital to the economic stability of the town. He was ordered to draw lists 20,000 Jews within four days. The Jews who received the exemption from deportation were allowed to return to their home. Popovici distributed authorizations to Jews, well above the quota he was given, and to people who had no professional skills whatsoever. In 1942, as a result of his actions, he was removed from his position and returned to Bucharest.

Prince Constantin worked through diplomatic channels to ensure the safety of Jews, thwarting thwart the deportation of many thousands of Romanian Jews from Vichy France as well as Hungarian Jews. Elena, the Queen Mother, organised the return from Transnistria of thousands of deported Jews, including thousands of Jewish orphans in 1943-1944. Antal hid a number of her Jewish neighbors. Anuţoiu warned the Jews that were going to be arrested in the communities of Bacău, Braşov, Odobeşti, Piatra-Neamţ, and Buzǎu, so that they were able to flee in time, and he also helped them find hiding places.

Dr. Dumitru Beceanu, a pharmacist, owned a pharmacy in Iaşi and was a reserve officer in the Romanian army. The Jewish pharmacists Dr. Leon and Rebeca Zisu and Dr. Simion Caufman worked in his pharmacy for years, and he continued to employ them during the war despite the promulgation of laws forbidding the employment of Jews. On June 29, 1941, during the pogrom, Beceanu urged his Jewish employees and some of his friends to hide in his apartment, which was above the pharmacy. About 20 Jews found shelter there.

Dr. Dumitru Beceanu, a pharmacist, owned a pharmacy in Iaşi and was a reserve officer in the Romanian army. The Jewish pharmacists Dr. Leon and Rebeca Zisu and Dr. Simion Caufman worked in his pharmacy for years, and he continued to employ them during the war despite the promulgation of laws forbidding the employment of Jews. On June 29, 1941, during the pogrom, Beceanu urged his Jewish employees and some of his friends to hide in his apartment, which was above the pharmacy. About 20 Jews found shelter there.

By the end of the Holocaust in Romania, the Germans, and their Hungarian and Romanian collaborators had murdered approximately 300,000 Romanian Jews, in addition to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian Jews. Such numbers make Romania directly responsible for more Jewish deaths in the Shoah than any other country, after Germany. Antonescu and several other officials of the Romanian wartime regime were tried after the war. Antonescu was convicted and executed. However, most Romanian perpetrators were never brought to justice. Romanian society has eschewed any real confrontation with its own role in the Holocaust and have generally worked to whitewash that history.

Mass emigration to Israel reduced the number of Jews in Romania. Those who remained suffered further persecution at the hands of the country’s new, Communist rulers, most notably in the early 1950s. Throughout the Communist period however, Romania allowed large numbers of Jews to emigrate to Israel, in exchange for much-needed Israeli economic aid. By 1987, there were just 27,000 Jews left in Romania. Further emigration since the 1989 revolution has reduced numbers even further. In 2016 there were 9,300-7,000 Jews live in Romania. Despite the dwindling number of Jews in Romania, synagogues and a religious infrastructure are maintained in many localities, including those in which only a handful of Jews are present.

Mass emigration to Israel reduced the number of Jews in Romania. Those who remained suffered further persecution at the hands of the country’s new, Communist rulers, most notably in the early 1950s. Throughout the Communist period however, Romania allowed large numbers of Jews to emigrate to Israel, in exchange for much-needed Israeli economic aid. By 1987, there were just 27,000 Jews left in Romania. Further emigration since the 1989 revolution has reduced numbers even further. In 2016 there were 9,300-7,000 Jews live in Romania. Despite the dwindling number of Jews in Romania, synagogues and a religious infrastructure are maintained in many localities, including those in which only a handful of Jews are present.

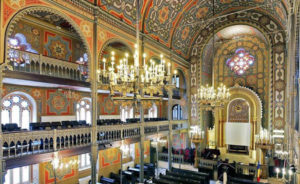

There are three Bucharest synagogues which still hold religious services (the Choral Temple, the Great Polish Synagogue and the Yeshoah Tova), as well as the Holy Union Temple which houses the Jewish History Museum. The Jewish cemetery of Jassy, has four long rows of massive cement slabs with Stars of David, symbolically marking the graves of the victims of the Jassy pogrom, which took place in late June 1941 and left thousands dead. As a plaque read: The victims were starved and suffocated in the “train of death” and elsewhere “butchered” by frenzied Iron Guardsmen and others.