The History of the Jews in Slovakia goes back to the 11th century, when the first Jews settled in the area. In the 14th century, about 800 Jews lived in Bratislava. In 1526, after the Battle of Mohács, Jews were expelled from all major towns but returned in late 17th century. In 1683, hundreds of Jews from Moravia fled to Slovakia, seeking refuge from Kuruc riots and restrictions on their living imposed in Moravia.

The History of the Jews in Slovakia goes back to the 11th century, when the first Jews settled in the area. In the 14th century, about 800 Jews lived in Bratislava. In 1526, after the Battle of Mohács, Jews were expelled from all major towns but returned in late 17th century. In 1683, hundreds of Jews from Moravia fled to Slovakia, seeking refuge from Kuruc riots and restrictions on their living imposed in Moravia.

In 1867, Slovakia became part of Austria-Hungary but in 1882 and 1883, there was antisemitic rioting. In 1896, the “Reception Law” was introduced. Under this law, Judaism and Christianity were placed on an equal level. After World War I and the creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918, Jews had the right to declare themselves a separate nationality and prospered in industry and cultural life.

In the 1930s, antisemitic rioting and demonstrations broke out again. During the rioting, professional Jewish boxers and wrestlers took to the streets to defend their neighbourhoods from antisemitic gangs, and one of them, Imi Lichtenfeld, would later use his experiences to develop Krav Maga. Before World War II, 135,000 Jews lived in Slovakia. After the Slovak Republic proclaimed its independence in March 1939 under the protection of Nazi Germany, Slovakia began a series of measures aimed against the Jews in the country, first excluding them from the military and government positions. The Hlinka Guard began to attack Jews, and the “Jewish Code” was passed in September 1941. Resembling the Nuremberg Laws, the Code required that Jews wear a yellow armband and were banned from many jobs. By 1940, more than 6,000 Jews had emigrated.

In the 1930s, antisemitic rioting and demonstrations broke out again. During the rioting, professional Jewish boxers and wrestlers took to the streets to defend their neighbourhoods from antisemitic gangs, and one of them, Imi Lichtenfeld, would later use his experiences to develop Krav Maga. Before World War II, 135,000 Jews lived in Slovakia. After the Slovak Republic proclaimed its independence in March 1939 under the protection of Nazi Germany, Slovakia began a series of measures aimed against the Jews in the country, first excluding them from the military and government positions. The Hlinka Guard began to attack Jews, and the “Jewish Code” was passed in September 1941. Resembling the Nuremberg Laws, the Code required that Jews wear a yellow armband and were banned from many jobs. By 1940, more than 6,000 Jews had emigrated.

The pro-Nazi regime of President Jozef Tiso, a Catholic priest, agreed to deport its Jews as part of the Nazi Final Solution. By October 1941, 15,000 Jews were expelled from Bratislava; many were sent to labor camps. Originally, the Slovak government tried to make a deal with Germany in October 1941 to deport its Jews as a substitute for providing Slovak workers to help the war effort. After the Wannsee Conference, the Germans agreed to the Slovak proposal, and a deal was reached where the Slovak Republic would pay for each Jew deported, and, in return, Germany promised that the Jews would never return to the republic. The initial terms were for “20,000 young, strong Jews”, but the Slovak government quickly agreed to a German proposal to deport the entire population for “evacuation to territories in the east”.

The pro-Nazi regime of President Jozef Tiso, a Catholic priest, agreed to deport its Jews as part of the Nazi Final Solution. By October 1941, 15,000 Jews were expelled from Bratislava; many were sent to labor camps. Originally, the Slovak government tried to make a deal with Germany in October 1941 to deport its Jews as a substitute for providing Slovak workers to help the war effort. After the Wannsee Conference, the Germans agreed to the Slovak proposal, and a deal was reached where the Slovak Republic would pay for each Jew deported, and, in return, Germany promised that the Jews would never return to the republic. The initial terms were for “20,000 young, strong Jews”, but the Slovak government quickly agreed to a German proposal to deport the entire population for “evacuation to territories in the east”.

The deportations of Jews from Slovakia started on March 25, 1942 (the first transport was made up solely of 999 young women; it was also the first mass transport of Jews to Auschwitz). Thery were halted on October 20, 1942. A group of Jewish activists led by Gisi Fleischmann and Rabbi Michael Ber Weissmandl tried, in vain, to stop the process through a mix of bribery and negotiation. However, some 58,000 Jews had already been deported by October 1942, mostly to the death camps in the General Gouvernment in occupied Poland and to Auschwitz. More than 99% of the 58 000 Jews deported from Slovakia in 1942 were murdered in the concentration and death camps.

Jewish deportations resumed on September 30, 1944, after German troops occupied the Slovak territory in order to defeat the Slovak National Uprising. During the German occupation, up to 13,500 Slovak Jews were deported (mostly to Auschwitz where most of them were gassed upon arrival), principally through the Jewish transit camp in Sereď under the command of Alois Brunner, and about 2,000 were murdered at the Slovak territory by members of the Einsatzgruppe H of the Sicherheitspolizei and the SD and their, mostly Slovak, collaborators. Deportations continued until March 31, 1945 when the last group of Jewish prisoners was taken from Sereď to the Terezín ghetto. In all, German and Slovak authorities deported about 70,000 Jews from Slovakia; about 65,000 of them were murdered or died in concentration camps.

Jewish deportations resumed on September 30, 1944, after German troops occupied the Slovak territory in order to defeat the Slovak National Uprising. During the German occupation, up to 13,500 Slovak Jews were deported (mostly to Auschwitz where most of them were gassed upon arrival), principally through the Jewish transit camp in Sereď under the command of Alois Brunner, and about 2,000 were murdered at the Slovak territory by members of the Einsatzgruppe H of the Sicherheitspolizei and the SD and their, mostly Slovak, collaborators. Deportations continued until March 31, 1945 when the last group of Jewish prisoners was taken from Sereď to the Terezín ghetto. In all, German and Slovak authorities deported about 70,000 Jews from Slovakia; about 65,000 of them were murdered or died in concentration camps.

Ludwig “Lali” Sokolov was an Austro-Hungarian-born Slovak-Australian businessman and a Holocaust survivor. He was Jewish, and having been sent to Auschwitz in 1942, served as the concentration camp’s Tätowierer (tattoo artist) until the camp was liberated near the end of World War II. Sokolov was a saviour who shared extra rations, altered prisoners tattoos to keep them from the gas chamber and helped doomed men pull off daredevil escapes. He believed that he was no hero but just trying to do the right thing.

Ludwig “Lali” Sokolov was an Austro-Hungarian-born Slovak-Australian businessman and a Holocaust survivor. He was Jewish, and having been sent to Auschwitz in 1942, served as the concentration camp’s Tätowierer (tattoo artist) until the camp was liberated near the end of World War II. Sokolov was a saviour who shared extra rations, altered prisoners tattoos to keep them from the gas chamber and helped doomed men pull off daredevil escapes. He believed that he was no hero but just trying to do the right thing.

During the deportations, some 6,000 Slovak Jews escaped to Hungary. On August 29, 1944, however, Slovak underground resistance organizations, Communist and non-Communist, rose against the Tiso regime as Soviet troops entered neighbouring sub-Carpathian Rus. With the fall of Bratislava on April 4th 1945 the liberation of Slovakia was completed. Vojtech Tuka and Jozef Tiso were arrested and sentenced to death. Tuka was executed August 20th 1946, followed by Tiso on April 18th 1947.

Marie Schmolka was a key player in one of the most remarkable rescue efforts of the Second World War, the kindertransports, which brought unaccompanied Jewish children out of Europe. However, her efforts begin in 1933, when the first refugees start coming to Czechoslovakia from Germany and she never stops. Marie Schmolka, together with her co-worker Hannah Steiner, issued numerous appeals, addressing Jews in the Free World and all kinds of institutions and organisations involved in helping the refugees.

Marie Schmolka was a key player in one of the most remarkable rescue efforts of the Second World War, the kindertransports, which brought unaccompanied Jewish children out of Europe. However, her efforts begin in 1933, when the first refugees start coming to Czechoslovakia from Germany and she never stops. Marie Schmolka, together with her co-worker Hannah Steiner, issued numerous appeals, addressing Jews in the Free World and all kinds of institutions and organisations involved in helping the refugees.

Schmolka was one of the first Jews arrested after occupation of Prague by the Germans a year ago. She was released, after being held more than two months, upon intervention with the Gestapo of the Czech Social Welfare Minister who acted at the instance of many international organizations. MShe went to London for conferences just before the outbreak of the war and was unable to return to Prague.

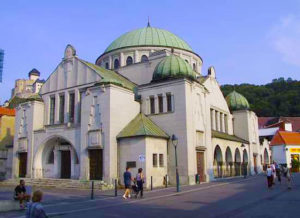

After the war, the number of Jews in Slovakia was estimated to 25,000. Most of them decided to emigrate. In 1948, Communist rule was established, lasting until 1989, and little or no Jewish life existed. Many Jews emigrated to Israel or the United States to regain their freedom of religion. After 1989, and with the peaceful breakup of Czechoslovakia and Slovak independence in 1993, there was some resurgence in Jewish life. Today, there are estimated 3,000 Jews in Slovakia. The majority of Slovak Jews live in Bratislava, the capital, but there are also Jewish communities in towns such as Košice, Prešov, Piešťany, Nové Zámky, Dunajská Streda, Galanta, Nitra, Žilina, Lučenec, Trenčín, Komárno, Banská Bystrica, and Humenné. Many young Jews have moved from their hometowns to larger cities, in order to find work or to study. This migration from community life to the city has somehow affected traditional lifestyles and religious observance among Slovak Jews. However, the synagogues in Bratislava and in Kosice are used regularly for services.

After the war, the number of Jews in Slovakia was estimated to 25,000. Most of them decided to emigrate. In 1948, Communist rule was established, lasting until 1989, and little or no Jewish life existed. Many Jews emigrated to Israel or the United States to regain their freedom of religion. After 1989, and with the peaceful breakup of Czechoslovakia and Slovak independence in 1993, there was some resurgence in Jewish life. Today, there are estimated 3,000 Jews in Slovakia. The majority of Slovak Jews live in Bratislava, the capital, but there are also Jewish communities in towns such as Košice, Prešov, Piešťany, Nové Zámky, Dunajská Streda, Galanta, Nitra, Žilina, Lučenec, Trenčín, Komárno, Banská Bystrica, and Humenné. Many young Jews have moved from their hometowns to larger cities, in order to find work or to study. This migration from community life to the city has somehow affected traditional lifestyles and religious observance among Slovak Jews. However, the synagogues in Bratislava and in Kosice are used regularly for services.