Jews lived in the Balkans from at least the first century CE, till the early twentieth century; waves of Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews came to the area — some as traders, many to flee persecution farther west. Synagogue ruins and graves along the Adriatic Coast place Jews of the late Roman Empire in Croatia nearly two thousand years ago. Evidence shows, too, that Byzantine oppression caused some Jews to relocate even farther east.

Jews lived in the Balkans from at least the first century CE, till the early twentieth century; waves of Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews came to the area — some as traders, many to flee persecution farther west. Synagogue ruins and graves along the Adriatic Coast place Jews of the late Roman Empire in Croatia nearly two thousand years ago. Evidence shows, too, that Byzantine oppression caused some Jews to relocate even farther east.

A radical change for Jews came in 1299, when the Ottoman Turks conquered Byzantium and launched their vast empire. While classifying Jews, as second-class citizens, the Turks safeguarded their minorities. This assured Jews better treatment than that under Byzantium. During the 13th-14th centuries, Jews lived in Zagreb and enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy with a leader called a “magistratus Jedaeorum.” During this period, Jewish communities prospered and they played a significant role in commerce. In 1456 they decided that the number of Jews was too large, so Jews were terrorized and then expelled from the region.

At the end of the 18th century Jews returned to Croatia, under the Hapsburgs. During this reign, Jewish settlement was allowed, and Jews arrived from Burgenland, Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary and elsewhere in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Jews had to contend with several restrictions until their full emancipation in 1870. From 1879 to 1900, the Jewish population in Croatia increased from 869 persons to 20,000.

At the end of the 18th century Jews returned to Croatia, under the Hapsburgs. During this reign, Jewish settlement was allowed, and Jews arrived from Burgenland, Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary and elsewhere in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Jews had to contend with several restrictions until their full emancipation in 1870. From 1879 to 1900, the Jewish population in Croatia increased from 869 persons to 20,000.

The problem of deporting Jews already appeared in the first months of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The government considered deportation necessary because the Ashkenazim were seen as foreign since they had come to the area of the new state from other parts of Austria-Hungary. Although some of them had been living in Croatia, Voivodina or Bosnia for several decades, the Yugoslav authorities felt that they had not gained the right to acquire citizenship. Thus, deportation began, although various Yugoslav and international Jewish organisations were engaged in preventing it at the Paris Peace Conference.

After World War I Croatia was already deporting Jews in the most brutal fashion: the first to suffer were the Bosnian Ashkenazim a small number of whom were banished. Others were allowed to return home after several months of moving from place to place but they suffered greatly in the material sense. The same problem arose in Zagreb, where there was a plan to exile 600 families in 24 hours, as well as in Voivodina. Jewish organisations began to intercede and the displacement was discontinued; some people, however, could not return to their homes.

After World War I Croatia was already deporting Jews in the most brutal fashion: the first to suffer were the Bosnian Ashkenazim a small number of whom were banished. Others were allowed to return home after several months of moving from place to place but they suffered greatly in the material sense. The same problem arose in Zagreb, where there was a plan to exile 600 families in 24 hours, as well as in Voivodina. Jewish organisations began to intercede and the displacement was discontinued; some people, however, could not return to their homes.

Things seemed to have cooled down as time passed and deportations from Zagreb and its surroundings decreased and finally stopped, but in the winter of 1919-1920 there was still deportation from Bosnia and people had to leave their homes in the freezing winter, although they had been living among them for several decades.

In 1922 there was a crisis in Voivodina when the Jews were treated as second-rate citizens: special police surveillance was organised and they were threatened with deportation from the country. King Alexander created a more beneficent age for the Jews in 1929. Antisemitic incidents almost disappeared for some years because of strong governmental control over the whole of society. The king visited Jewish institutions several times and liked to be publicly shown as a friend of the Jews. The territory as a whole became part of Yugoslavia following World War I; by 1939 it had a Jewish population of around 25,000.

In 1922 there was a crisis in Voivodina when the Jews were treated as second-rate citizens: special police surveillance was organised and they were threatened with deportation from the country. King Alexander created a more beneficent age for the Jews in 1929. Antisemitic incidents almost disappeared for some years because of strong governmental control over the whole of society. The king visited Jewish institutions several times and liked to be publicly shown as a friend of the Jews. The territory as a whole became part of Yugoslavia following World War I; by 1939 it had a Jewish population of around 25,000.

In 1940, open discrimination started. There were two decrees, the first to prevent Jews from all wholesale enterprises dealing in food and reducing all education to the percentage of the Jews in the total population. NDH Interior Minister Andrija Artuković said in 1941 upon the proclamation of racial laws: “The Government of NDH shall solve the Jewish question in the same way as the German Government did”. Already in April 1941, the Ustaše and Volksdeutche burned the synagogue and destroyed the Jewish cemetery in Osijek, while the Ustaše mayor of Zagreb, Ivan Werner, ordered the destruction of the main Zagreb synagogue, which was completely razed in 1942. The Ustaše set up a number of concentration camps with the most notorious being Jasenovac in which 20,000 Jews were murdered.

Italian Fascists, however, occupied the coast, and were adamant about not turning over the refugees, because if they were to fall into the hands of the Croatians, they would be transported to the Jasenovac concentration camp, and “the consequences are well-known to everyone”. They used delaying tactics against both the Croatians and Germans and falsified data to prevent this happening. Only 5,000 Croatian Jews survived the war, most as soldiers in Josip Broz Tito’s National Liberation Army or as exiles in the Italian-occupied zone. After Italy capitulated to the Allied Powers, the surviving Jews lived in free Partisan territory.

Italian Fascists, however, occupied the coast, and were adamant about not turning over the refugees, because if they were to fall into the hands of the Croatians, they would be transported to the Jasenovac concentration camp, and “the consequences are well-known to everyone”. They used delaying tactics against both the Croatians and Germans and falsified data to prevent this happening. Only 5,000 Croatian Jews survived the war, most as soldiers in Josip Broz Tito’s National Liberation Army or as exiles in the Italian-occupied zone. After Italy capitulated to the Allied Powers, the surviving Jews lived in free Partisan territory.

Some of the people who helped the Jews includes: Ratimir Deletis, Žarko & Boris Dolinar, Jozica Jurin, Miroslav Kirec, Franjo Sopianac, Ivan Vranetić, Antun Vuletić & Stanko Sielski.

Ratimir Deletis, a lawyer, was appointed to the state attorney’s office and, in this capacity, he could help some Jews. Only those Jews who had official exemptions were able to remain in the cities, and these exemptions could only be acquired through the mediation of Croats influential with the authorities in Zagreb. Deletis decided to go to Zagreb in order to talk with Eugen Dido Kvaternik, the head of the Ustaša security services, to persuade him to abolish the deportation orders. He negotiated the release of 16 Jewish families if they converted to Islam or Christianity. The local authorities added people to these families, thus 100 Jews were saved.

Ratimir Deletis, a lawyer, was appointed to the state attorney’s office and, in this capacity, he could help some Jews. Only those Jews who had official exemptions were able to remain in the cities, and these exemptions could only be acquired through the mediation of Croats influential with the authorities in Zagreb. Deletis decided to go to Zagreb in order to talk with Eugen Dido Kvaternik, the head of the Ustaša security services, to persuade him to abolish the deportation orders. He negotiated the release of 16 Jewish families if they converted to Islam or Christianity. The local authorities added people to these families, thus 100 Jews were saved.

Žarko Dolinar, a sports coach for the Maccabi Sports Club lived in Zagreb. After winning a gold medal, and after the German invasion in April 1941, he took advantage of this and during visits at Ustaša headquarters, he stole blank identity papers and seals. He and his brother, Boris, created travel permits and identity papers for a large number of Jews. When the roundup of young Jews began in June 1941, the Dolinar brothers worked very hard to rescue as many young Jews as possible.

Žarko Dolinar, a sports coach for the Maccabi Sports Club lived in Zagreb. After winning a gold medal, and after the German invasion in April 1941, he took advantage of this and during visits at Ustaša headquarters, he stole blank identity papers and seals. He and his brother, Boris, created travel permits and identity papers for a large number of Jews. When the roundup of young Jews began in June 1941, the Dolinar brothers worked very hard to rescue as many young Jews as possible.

Jozica Jurin, known as Sister Cecilija, was mother superior in a Catholic convent in Split. During the war, the convent was used as a shelter for refugees, among them Jewish children and others persecuted by the Germans. Twelve nuns lived there and looked after 50 children. There were eight Jewish children sheltered at the convent, who were were hidden from the Nazis.

Miroslav Kirec, a Croatian, was involved with the communist underground in Belgrade. In June 1941, two months after the Germans entered Yugoslavia, male Jews were rounded up. Kirec was designated by the underground to try and rescue Jews. He arranged for the temporary dispersal of Jews to the homes of Serbian friends so they could avoid the roundups. He continued with this work until mid-1942.

Miroslav Kirec, a Croatian, was involved with the communist underground in Belgrade. In June 1941, two months after the Germans entered Yugoslavia, male Jews were rounded up. Kirec was designated by the underground to try and rescue Jews. He arranged for the temporary dispersal of Jews to the homes of Serbian friends so they could avoid the roundups. He continued with this work until mid-1942.

Franjo Sopianac, owner of the Olex oil refinery plant, lived with his wife, Lela, and their son Ivan in Zagreb. In April 1941, when anti-Jewish laws were announced and deportation orders posted, Sopianac rescued Jews and used his factory buildings, as a hiding place for them and their families. With the outbreak of fighting, the factory had closed, but the Ustaša decided to reopen the factory for military purposes. Sopianac acquired work permits as essential workers for the younger men and women staying in the factory. His family took care of the elderly Jews and the children, who could not work who were hidden in the plant, or in their own home. Lela also obtained several travel permits that enabled some Jews to flee to the Italian occupied zone.

Ivan Vranetić was 17 when he witnessed the arrival of many Jews, in Topusko. In September 1943, following the Italian surrender to the Allies, Yugoslav partisans went to evacuate the Jews held in the internment camp on the Adriatic island of Rab. Most of the men joined the partisans, while mothers with children and the infirm were placed in the villages under partisan control. Vranetić helped the Jewish refugees and found places for them to live. Vranetić always warned the Jews in advance of an approaching front, he found them new hiding places, escorted them there, and took care of all their needs.

Ivan Vranetić was 17 when he witnessed the arrival of many Jews, in Topusko. In September 1943, following the Italian surrender to the Allies, Yugoslav partisans went to evacuate the Jews held in the internment camp on the Adriatic island of Rab. Most of the men joined the partisans, while mothers with children and the infirm were placed in the villages under partisan control. Vranetić helped the Jewish refugees and found places for them to live. Vranetić always warned the Jews in advance of an approaching front, he found them new hiding places, escorted them there, and took care of all their needs.

When the Germans entered Zagreb in April 1941, the Ustaša took control, and in July 1941, the roundup of Jews began. They first targeted Jewish intellectuals, lawyers, and doctors. At around the same time, the head of the health services in Bosnia requested that as many doctors as possible be sent to Bosnia to treat the spread of contagious diseases, in particular endemic syphilis. Dr. Miroslav Schlesinger heard about this and saw in it an opportunity to rescue his Jewish colleagues.  He asked his friend Dr. Ante Vuletić, a specialist in contagious diseases, to speak to the authorities. Vuletić lobbied for this deficit to be covered by sending the Jewish doctors to Bosnia where they could treat patients. The authorities eventually decided to accept Vuletić’s proposal and 68 doctors were chosen to go to Bosnia with their families. In all, this amounted to about 200 Jews being freed.

He asked his friend Dr. Ante Vuletić, a specialist in contagious diseases, to speak to the authorities. Vuletić lobbied for this deficit to be covered by sending the Jewish doctors to Bosnia where they could treat patients. The authorities eventually decided to accept Vuletić’s proposal and 68 doctors were chosen to go to Bosnia with their families. In all, this amounted to about 200 Jews being freed.

Vuletić was joined in his efforts by Dr. Stanko Sielski, who issued transfer orders to Jewish doctors, in which he wrote that the transfer had allegedly been ordered by the Ministry of Interior. The Jewish doctors were dispersed, mainly among the villages of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The majority of Jewish doctors and their families survived the war with the help of Dr. Sielski. They went to join the Partisans or to the liberated areas.

Vuletić was joined in his efforts by Dr. Stanko Sielski, who issued transfer orders to Jewish doctors, in which he wrote that the transfer had allegedly been ordered by the Ministry of Interior. The Jewish doctors were dispersed, mainly among the villages of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The majority of Jewish doctors and their families survived the war with the help of Dr. Sielski. They went to join the Partisans or to the liberated areas.

In the post-war period, first came Tito‘s communist government, which severely restricted ethnic and religious expressions, nationalized all religious real estate, including the land on which the synagogue once stood, and in 1967 severed ties with Israel. Yet even after the fall of Communism in 1989, and Croatia’s long-dreamed-for independence, little changed for its Jews, who could not regain their property. In 2012, a report from the European Shoah Legacy Institute found recovering Jewish property in Croatia problematic.

Croatia’s Jewish community numbers 1,700. Although there have been difficulties in combating anti-Semitism and other problematic ideologies in the country, in particular historical revisionism that has sought to rehabilitate the fascist Ustasha movement of the 1930’s and 1940’s and cleanse it of responsibility for the mass killing of Jews and Serbs during World War II, Croatian Jewry enjoys full and equal rights along with support from the government.

Croatia’s Jewish community numbers 1,700. Although there have been difficulties in combating anti-Semitism and other problematic ideologies in the country, in particular historical revisionism that has sought to rehabilitate the fascist Ustasha movement of the 1930’s and 1940’s and cleanse it of responsibility for the mass killing of Jews and Serbs during World War II, Croatian Jewry enjoys full and equal rights along with support from the government.

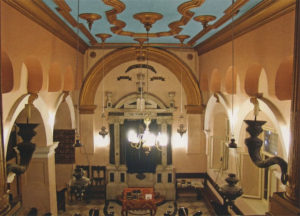

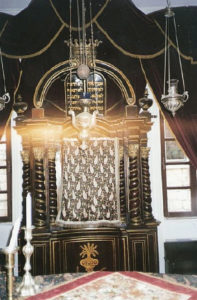

Three quarters of Croatia’s Jews live in the capital of Zagreb, with other small communities in Osijek, Rijeka, Split, and Dubrovnik. The Hugo Kon Elementary School is the only Jewish day school in Croatia. The Jewish community also sponsors a kindergarten, Sunday school and Hebrew language courses. There is a sizeable synagogue in Zagreb that has its own permanent rabbi. An alternate Orthodox Jewish community in Zagreb called Bet Israel has its own rabbi, and prayer room.