The history of Spanish Jewry dates back at least 2,000 years. The Golden Age of Spanish Jewry took place in the southern region of Andalusia from the 9th through 12th centuries, during which a network of Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars laid the groundwork for the Renaissance. During the subsequent centuries, a succession of intolerant Muslim invaders from North Africa and Christian reconquerers made life increasingly difficult for Jews, and by 1391, Jewish society came to an end. The persecution continued through the 15th century, rising to the crescendo of 1492, sending Jews fleeing into exile.

The history of Spanish Jewry dates back at least 2,000 years. The Golden Age of Spanish Jewry took place in the southern region of Andalusia from the 9th through 12th centuries, during which a network of Jewish, Christian and Muslim scholars laid the groundwork for the Renaissance. During the subsequent centuries, a succession of intolerant Muslim invaders from North Africa and Christian reconquerers made life increasingly difficult for Jews, and by 1391, Jewish society came to an end. The persecution continued through the 15th century, rising to the crescendo of 1492, sending Jews fleeing into exile.

Spanish Jewry once constituted one of the largest and most prosperous communities under Moslem and Christian rule in Spain, numbering as many as 235,000, before the majority were forced to convert to Catholicism, expelled or killed when Catholic Spain was unified following the marriage of Isabella de Castilla to Ferdinand de Aragon.The Inquisition was introduced in 1481, and antisemitism peaked under their rule. By 1492, more than 100,000 Jews had fled Spain. After the Expulsion, some of the Conversos escaped to Western Europe and Latin America, where they could revert to the open practice of Judaism.The Inquisition was abolished only in 1834.

After hundreds of years abroad, Jews were finally permitted to return to Spain after the abolition of the Inquisition in 1834 and the creation of a new constitutional monarchy that allowed for the practice of faiths other than Catholicism in 1868, though the edict of expulsion was not repealed until 1968. The Spanish Moroccan War of 1859-60 also brought many Jews to southern Spain who were fleeing Morocco. Small numbers of Jews started to arrive in Spain in the 19th century, and synagogues were eventually opened in Madrid and Barcelona. Slowly things began to improve and Spanish historians even started to take an interest in the history of Spain’s Jewish population and in the Sephardic language of Ladino. In 1917, the Jews of Madrid numbers around 1,000 people. Most were German, Austrian-Hungarian and Turkish citizens who fled to Spain at the beginning of World War I. They inaugurated their first synagogue in a small apartment. The world economic crisis of 1929 brought additional Jews to the country. Under the Second Republic (1931-36), whose constitution guaranteed religious liberty and affirmed the secular character of the state, Spain aroused considerable interest among Jews in Europe and the Orient, who saw this guarantee as tantamount to an abrogation of the expulsion decree.

After hundreds of years abroad, Jews were finally permitted to return to Spain after the abolition of the Inquisition in 1834 and the creation of a new constitutional monarchy that allowed for the practice of faiths other than Catholicism in 1868, though the edict of expulsion was not repealed until 1968. The Spanish Moroccan War of 1859-60 also brought many Jews to southern Spain who were fleeing Morocco. Small numbers of Jews started to arrive in Spain in the 19th century, and synagogues were eventually opened in Madrid and Barcelona. Slowly things began to improve and Spanish historians even started to take an interest in the history of Spain’s Jewish population and in the Sephardic language of Ladino. In 1917, the Jews of Madrid numbers around 1,000 people. Most were German, Austrian-Hungarian and Turkish citizens who fled to Spain at the beginning of World War I. They inaugurated their first synagogue in a small apartment. The world economic crisis of 1929 brought additional Jews to the country. Under the Second Republic (1931-36), whose constitution guaranteed religious liberty and affirmed the secular character of the state, Spain aroused considerable interest among Jews in Europe and the Orient, who saw this guarantee as tantamount to an abrogation of the expulsion decree.

During World War II, neutral Spain became the only refuge in southern Europe from the lightning advance of the Nazi troops. Spanish neutrality in World War II allowed 25,600 Jews to use Spain as a getaway, with Franco allowing Jews to use the country as an escaping route. Initially, transit visas were fairly easy to obtain. After the armistice of 1940, however, Spain and France took measures to regulate requests, especially through the Spanish consulate in Marseille. After July 1942 it was illegal for Jews to leave France, and so the crossings were made in secret, albeit with a degree of Spanish sympathy. Nevertheless, there were arrests, and a camp was established at Miranda de Ebro, where prisoners received psychological and material help from American Jewish organisations based in Madrid. These prisoners were gradually evacuated, most of them to Lisbon and the United States.

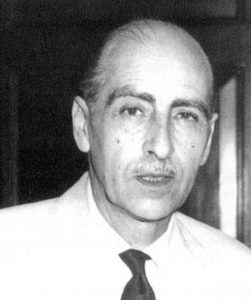

Eduardo Propper de Callejón was a Spanish diplomat who is mainly remembered for having facilitated the escape of thousands of Jews from occupied France during World War II between 1940 and 1944. He was the father-in-law of British banker Raymond Bonham Carter and the maternal grandfather of British actress Helena Bonham Carter. He issued transit visas to the refugees. For four days between 18- 22 June 1940 he incessantly stamped passports. By doing so, he was defying the instructions not to issue visas without prior approval of the Foreign Ministry.

Eduardo Propper de Callejón was a Spanish diplomat who is mainly remembered for having facilitated the escape of thousands of Jews from occupied France during World War II between 1940 and 1944. He was the father-in-law of British banker Raymond Bonham Carter and the maternal grandfather of British actress Helena Bonham Carter. He issued transit visas to the refugees. For four days between 18- 22 June 1940 he incessantly stamped passports. By doing so, he was defying the instructions not to issue visas without prior approval of the Foreign Ministry.

Propper continued to provide visas at the embassy’s new seat in Vichy, It is unknown how many visas Propper de Callejon issued, because the consulate’s registry did not survive. In March 1941, Foreign Minister Ramon Serrano Suner informed the Spanish Ambassador to France José Lucresia that Propper was to be transferred to Spanish Morocco.

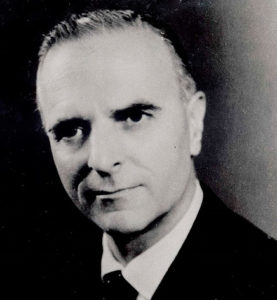

Angel Sanz-Briz, was appointed to the post of chargè d’affaires at the Spanish Legation in the summer of 1944. As soon as the persecutions of the Hungarian Jews began, he offered, to supply Jews of Spanish origin with Spanish passports and to negotiate with the Hungarian government for their protection. Sanz-Briz received the consent of the Hungarian authorities to enable 200 Spanish Jews to receive these rights, but he changed it to 200 families and then enlarged this group again and again. Sanz-Briz also accommodated Jews in rented buildings in Budapest under the Spanish flag, putting up signs that those buildings were extra-territorial property belonging to the Spanish Legation. He also prompted the International Red Cross representative to put Spanish signs in Budapest on hospital buildings, as well as orphanages and maternity clinics, to protect the Jews therein. Sanz-Briz acted heroically and succeeded in saving a great number of Jews, most of them not of Spanish origin. Sanz-Briz was ordered by his government to leave the Hungarian capital in December 1944.

Angel Sanz-Briz, was appointed to the post of chargè d’affaires at the Spanish Legation in the summer of 1944. As soon as the persecutions of the Hungarian Jews began, he offered, to supply Jews of Spanish origin with Spanish passports and to negotiate with the Hungarian government for their protection. Sanz-Briz received the consent of the Hungarian authorities to enable 200 Spanish Jews to receive these rights, but he changed it to 200 families and then enlarged this group again and again. Sanz-Briz also accommodated Jews in rented buildings in Budapest under the Spanish flag, putting up signs that those buildings were extra-territorial property belonging to the Spanish Legation. He also prompted the International Red Cross representative to put Spanish signs in Budapest on hospital buildings, as well as orphanages and maternity clinics, to protect the Jews therein. Sanz-Briz acted heroically and succeeded in saving a great number of Jews, most of them not of Spanish origin. Sanz-Briz was ordered by his government to leave the Hungarian capital in December 1944.

In 1941, the government paradoxically set up the Instituto Arias Montano, which became one of the most renowned centres for the study of Spanish Judaism. In 1949 a small synagogue opened discreetly in a Madrid apartment. The same happened in Barcelona in 1952. Although Catholicism was now the state religion, these small communities were tolerated. In 1967 a synagogue was built in Madrid, the first one since 1492. In 1978, Spain’s new constitution guaranteed religious freedom to all citizens. Spanish diplomats such as Ángel Sanz Briz and Giorgio Perlasca protected some 4,000 Jews in France and the Balkans. In 1944, Spain accepted 2,750 Jewish refugees from Hungary. Later, as the Franco regime evolved, synagogues were opened and the communities were permitted to hold services discreetly. Between 1948, the year Israel was created, and 2010, 1747 Spanish Jews made aliyah to Israel.

In 1941, the government paradoxically set up the Instituto Arias Montano, which became one of the most renowned centres for the study of Spanish Judaism. In 1949 a small synagogue opened discreetly in a Madrid apartment. The same happened in Barcelona in 1952. Although Catholicism was now the state religion, these small communities were tolerated. In 1967 a synagogue was built in Madrid, the first one since 1492. In 1978, Spain’s new constitution guaranteed religious freedom to all citizens. Spanish diplomats such as Ángel Sanz Briz and Giorgio Perlasca protected some 4,000 Jews in France and the Balkans. In 1944, Spain accepted 2,750 Jewish refugees from Hungary. Later, as the Franco regime evolved, synagogues were opened and the communities were permitted to hold services discreetly. Between 1948, the year Israel was created, and 2010, 1747 Spanish Jews made aliyah to Israel.

The Jewish community is centred in Madrid with around 12,000 Jews. Barcelona also has a sizeable Jewish community of 5,000 members. In addition, Jewish congregations, including a handful of Conservative and Reform communities, can be found in cities such as Valencia, Malaga, and Marbella as well as the Spanish North African enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

In 2007, a modern Orthodox synagogue was established in the city of Alicante on the Costa Blanca, where about 1,000 Jews reside. There are also Jewish day schools in Madrid, Barcelona and Melilla.

In 2007, a modern Orthodox synagogue was established in the city of Alicante on the Costa Blanca, where about 1,000 Jews reside. There are also Jewish day schools in Madrid, Barcelona and Melilla.

More recently, Jewish immigrants have moved from Latin America, especially Argentina and Venezuela. The Spanish Jewish community is one of the few Jewish communities in Western Europe that is growing in both numbers and activities. The Spanish government has made an increased effort to increase the awareness of the role that the Jews once played in Spanish life and to combat anti-Semitism.

The Spanish Parliament approved a measure on June 11, 2015, aimed at restoring citizenship to descendants of Sephardic Jewish individuals who were expelled during the Inquisition.