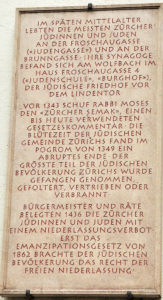

The first Jewish communities settled in Basel in 1214. Jews were the victims of persecution during the Black Plague, which they were supposed to have caused. In 1349, 600 Jews in Basel were burned at the stake and 140 children forcibly converted to Catholicism, while in Zürich Jews’ belongings were confiscated and a number of Jews were burned at the stake.

The first Jewish communities settled in Basel in 1214. Jews were the victims of persecution during the Black Plague, which they were supposed to have caused. In 1349, 600 Jews in Basel were burned at the stake and 140 children forcibly converted to Catholicism, while in Zürich Jews’ belongings were confiscated and a number of Jews were burned at the stake.

From 1776, Jews were allowed to reside exclusively in two villages, Lengnau and Oberendingen, in what is now the canton of Aargau. At the close of the 18th century, the 553 Jews in these villages represented almost the entire Jewish population in Switzerland. In 1750, Jews were allowed to buy woodland on a hill between Endingen and Lengnau for a cemetery. Both Lengnau and Endingen had their own synagogues.

The Jewish residents of the two towns were constrained in terms of the professions they could follow. Houses were constructed with two separate entrances, one for gentiles and one for Jews. Jews from the towns had to pay special taxes including a “firewood” tax. In 1802 a portion of the population revolted and turned against the Jews. The mob looted the Jewish villages of Endingen and Lengnau in the so-called Zwetschgenkrieg (“Plum war”).

The Jewish residents of the two towns were constrained in terms of the professions they could follow. Houses were constructed with two separate entrances, one for gentiles and one for Jews. Jews from the towns had to pay special taxes including a “firewood” tax. In 1802 a portion of the population revolted and turned against the Jews. The mob looted the Jewish villages of Endingen and Lengnau in the so-called Zwetschgenkrieg (“Plum war”).

By the mid 19th century things began to change for the better and Jews began to leave setting their sights on Zürich and Basel. In 1862, the Jewish community of Zürich, the Israelitische Cultusgemeinde Zürich (ICZ) was founded, and in 1884, the Zürich Synagogue was built at the Löwenstrasse. In 1876, the Jews were granted full equality in civil rights and allowed to travel. However, ritual slaughter – Kosher Shechita, was prohibited and this prohibition has never been lifted.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Jews from Alsace, Germany and Eastern Europe arrived. In 1920, the Jewish population had reached its peak at 21,000 people, a figure that has remained almost constant ever since. After the First World War, Jews in Switzerland came under severe threat from antisemitism, which became more and more severe in each decade that followed. Right before World War II, there were 18,000 Jews living in Switzerland.

During the Holocaust, most Jews were sent back to the Nazis or put in what were essentially slave labour camps, which held an estimated 22,500 men, women and children. Many families were separated by police, including, in some cases, nursing infants from their mothers. Men as old as 60 were made to haul logs in forests or dig ditches on roads in the Alps, including during the harsh Swiss winter. Women were often assigned to institutions and private homes to mop floors and clean toilets. Living conditions in unheated barns or wooden barracks were spartan at best. Male inmates might be insulted with anti-Semitic remarks or forced to carry out tasks beyond their physical strength. Refugees who complained could be sent to punishment camps or deported to Auschwitz.

During the Holocaust, most Jews were sent back to the Nazis or put in what were essentially slave labour camps, which held an estimated 22,500 men, women and children. Many families were separated by police, including, in some cases, nursing infants from their mothers. Men as old as 60 were made to haul logs in forests or dig ditches on roads in the Alps, including during the harsh Swiss winter. Women were often assigned to institutions and private homes to mop floors and clean toilets. Living conditions in unheated barns or wooden barracks were spartan at best. Male inmates might be insulted with anti-Semitic remarks or forced to carry out tasks beyond their physical strength. Refugees who complained could be sent to punishment camps or deported to Auschwitz.

When thousands of Jews sought refuge in Switzerland during World War II, many Swiss residents helped them cross the border into safety. But at the time offering help was a crime. There are lots of people who did a lot to help the refugees. In 1942, Jakob Spirig was arrested by Swiss police. The 23-year-old was charged with helping Jewish refugees, including four older women from Berlin, cross the border into Switzerland, where they would be safe from persecution by the Nazis. Thousands of Jews from Germany and Austria were saved from murder in the Nazi concentration camps by Swiss residents who helped the refugees. Switzerland provided a safe haven for approximately 300,000 refugees during the Nazi period. Spirig, and many others like him, was sentenced by a military court to years in prison and he served the sentence to the last day.

When thousands of Jews sought refuge in Switzerland during World War II, many Swiss residents helped them cross the border into safety. But at the time offering help was a crime. There are lots of people who did a lot to help the refugees. In 1942, Jakob Spirig was arrested by Swiss police. The 23-year-old was charged with helping Jewish refugees, including four older women from Berlin, cross the border into Switzerland, where they would be safe from persecution by the Nazis. Thousands of Jews from Germany and Austria were saved from murder in the Nazi concentration camps by Swiss residents who helped the refugees. Switzerland provided a safe haven for approximately 300,000 refugees during the Nazi period. Spirig, and many others like him, was sentenced by a military court to years in prison and he served the sentence to the last day.

Switzerland was supposedly neutral during the Second World War, however, the Swiss government had adopted an anti-semitic asylum policy during the war, driving back thousands of refugees by requiring that Germany issue a “J” stamp on the passports of its Jewish nationals. Swiss banks finally admitted having wrongfully confiscated accounts belonging to victims of the Shoah, while insurance companies were accused of failing to pay premiums to the appropriate parties after the war.

Switzerland was supposedly neutral during the Second World War, however, the Swiss government had adopted an anti-semitic asylum policy during the war, driving back thousands of refugees by requiring that Germany issue a “J” stamp on the passports of its Jewish nationals. Swiss banks finally admitted having wrongfully confiscated accounts belonging to victims of the Shoah, while insurance companies were accused of failing to pay premiums to the appropriate parties after the war.

Tens of thousands of Holocaust survivors and relatives were unable to collect money deposited in Swiss accounts because of bureaucratic parsimony and outright fraud. In 1998, the country’s two largest banks agreed to pay $1.2-billion to settle claims by Holocaust survivors who had been unable to collect money from their bank accounts. In December, an panel of eminent historians lambasted the country’s refusal to admit Jewish refugees beginning in 1938 as a blatant example of anti-Semitism.

Currently Switzerland has about 20,000 Jews mostly in Zürich, Geneva, Basel and Vaud. There are more than 20 Jewish day schools in Switzerland.